Sage in Hastings: Smoke, Story, Science, and the Ethics of a Sacred Plant

Indigenous sage bundles are available at Pure Serenity Wellness Center, a shop located in Historic Downtown Hastings, Minnesota.

Executive summary

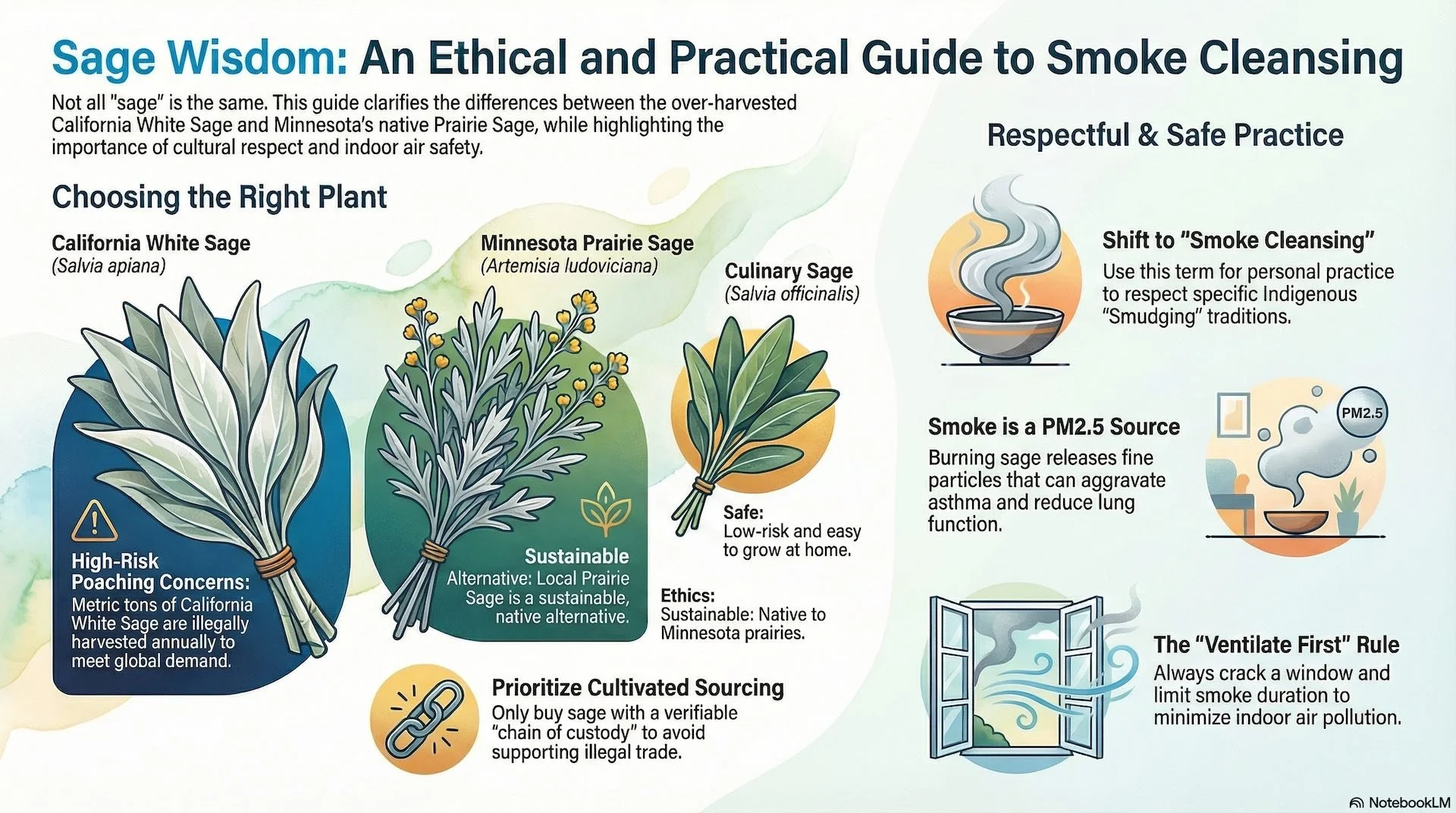

Sage is not a single plant. In everyday English, “sage” can mean aromatic plants in the mint family (the genus Salvia), several “sagebrush” species in the daisy family (the genus Artemisia), and—especially in modern wellness contexts—bundles sold for smoke cleansing. That linguistic blur matters, because the ecology, cultural significance, and ethical sourcing questions are radically different depending on which “sage” you’re holding.

For residents of Hastings, the most locally grounded “sage” for smoke cleansing is often prairie sage / white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), a plant that grows in Minnesota and is documented in Indigenous ethnobotany and plant guides as having medicinal and ceremonial uses (including smudges).

By contrast, the “white sage” that dominates national smudge-stick sales is typically California white sage (Salvia apiana), a shrub naturally occurring in Southern California and northern Baja California. It is deeply rooted in the lifeways of Indigenous communities in that region, and its commercialization is associated with persistent concerns about poaching, opaque supply chains, and cultural appropriation.

Smudging itself is not a single universal ritual. Many cultures use smoke, incense, and aromatic plants for ceremony. But “smudging” is also a specific constellation of Indigenous practices (varying by Nation/community) with protocols—such as asking permission from the plant and making an offering—described in Dakota ethnobotanical teaching materials and in broader Indigenous guidance.

Science does not cleanly “prove” the spiritual claims people attach to burning sage, and it also does not justify casual, frequent indoor smoke exposure. Peer‑reviewed research suggests that burning incense is a significant indoor particle source (PM2.5), and health agencies emphasize that fine particles can aggravate asthma and reduce lung function. Smoke cleansing should be treated like any other indoor combustion source: minimize dose, ventilate, and consider smoke‑free alternatives for anyone with respiratory sensitivity.

A Hastings prologue

In a river town, smoke is never just smoke. It is woodstoves and backyard fire rings, autumn leaves and incense, grills and candles—each one a small declaration that the indoors and outdoors still talk to each other. In Hastings, where the bluffs and water shape daily life, it’s easy to understand why people reach for scent as a way to mark transitions: the end of winter, a move to a new home, a grief that won’t quite leave, a new relationship, a new beginning.

But the modern “sage boom” arrived with a hidden geography. A bundle bought in Minnesota may trace back—ecologically and culturally—to landscapes far away, including habitat where California white sage naturally occurs, and to communities for whom that plant is not a décor trend but a relative, a medicine, and a practice shaped by survival through suppression.

Place matters for another reason: Minnesota has its own “sage.” Prairie sage / white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana) is documented as occurring in Minnesota prairies and is widely distributed as a native plant. For Hastings residents, this creates a rare opportunity: you can align a personal ritual with a plant that is actually part of the broader regional ecology rather than an over‑pressured, far‑away commodity.

And “place” matters spiritually for the first peoples of this region. Dakota history and living Dakota community sources emphasize long relationships with land and waterways in what is now Minnesota. MNopedia, for example, describes Dakota significance tied to confluences, and Dakota cultural organizations describe Dakota presence in the region across deep time. This context is not an aesthetic backdrop; it is the ethical ground beneath any conversation about “Indigenous plants” and “Indigenous practices.”

Timeline

c. 300 BCE: Greek botanical writing distinguishes wild vs. cultivated 'sage'

c. 50–70 CE: Dioscorides catalogs medicinal uses of sage-like plants

c. 70–80 CE: Pliny records Roman 'salvia' remedies and uses

c. 800 CE: Carolingian estate lists include sage for cultivation

Medieval Europe: sage becomes emblematic 'savior' herb in monastic & folk traditions

1753: Linnaean taxonomy formalizes Salvia officinalis in modern binomials

1800s–1900s: Ethnobotanical documentation records diverse Indigenous sage/sagebrush uses

1978: Federal U.S. policy affirms protection of Indigenous ceremonial religious practice

2010s–2020s: Global wellness trend fuels demand; white sage poaching concerns intensify

Origins and ethnobotany

What “sage” means in historical records

Botanically, “sage” often points to the genus Salvia, the largest genus in the mint family (Lamiaceae), with on the order of ~1,000 accepted species in contemporary taxonomic treatments.

In Europe, the “classic” culinary and medicinal sage is garden/common sage (Salvia officinalis), native to parts of southern/central Europe and long cultivated for food and medicine. Kew’s Plants of the World Online lists its native range as stretching from southwestern Germany to southern Europe.

Ancient and medieval European herb traditions frequently elevated sage with language that sounds almost mythic—because it sat at the intersection of food, medicine, preservation, and ritual. The Medieval Garden Enclosed (a scholarly museum blog by The Metropolitan Museum of Art) documents the “Why should a man die…?” tradition of sage-as-longevity language within medieval herb culture, capturing how people framed sage as both practical and near‑sacred.

When you zoom out, the “origin story” of sage is less a single beginning than a braided archive: Greek and Roman botanical medicine, monastic garden culture, early modern herbals, and domestic practice. That braid helps explain why modern people reach for sage when they are searching for a ritual that feels older than their stress.

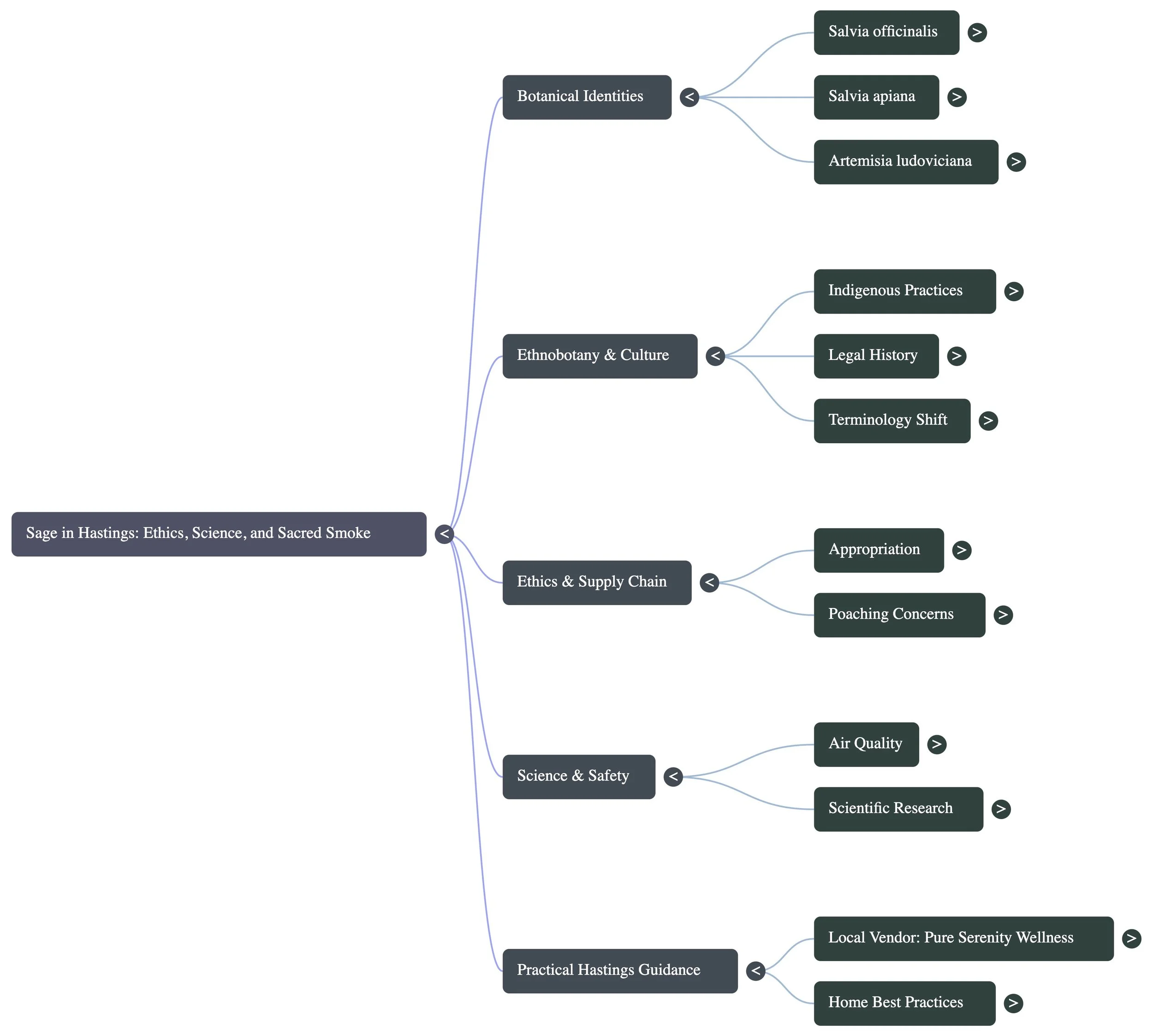

AI mind map by HastingsNow.com

What “sage” means in Indigenous ethnobotany near Minnesota

In North America, the situation is more complex—and more important.

Many Indigenous communities across the Plains and Great Lakes have longstanding ceremonial and medicinal relationships not only with Salvia species, but also with “sage” plants in the Artemisia genus (Asteraceae), often called sagebrush, wormwood, or prairie sage. The key Hastings‑relevant plant here is:

Prairie sage / white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), which Minnesota plant resources describe as the subspecies occurring in Minnesota and widely distributed.

The Artemisia ludoviciana plant guide in the USDA PLANTS system explicitly documents ceremonial and practical uses across multiple Nations, including reference to “a smudge” of the leaves used to drive away mosquitoes, and it describes the plant’s distribution across wide swaths of North America.

For Great Lakes ethnobotany, the public‑domain text Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians records “white sage (Artemisia ludoviciana)” in Ojibwe plant use documentation, offering a window into how smoke (smudging) and plant knowledge were embedded in daily practice and spiritual protection.

For Dakota‑centered teaching materials, an ethnobotanical guide prepared in an academic setting describes sage (with cedar, sweetgrass, and tobacco) as among the “four sacred plants,” and describes smudging as burning a bundle of sage to cleanse a setting (with associated protocols such as offering tobacco and asking permission).

This is crucial for Hastings residents because it reframes the question “Should I burn sage?” into two better questions:

Which plant are you burning? and

Which cultural meaning are you borrowing, honoring, or accidentally distorting by how you name and perform the act?

The legal shadow behind modern “smudging” conversations

If the debate around sage sometimes feels unusually charged, part of the reason is legal history. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) established federal policy to protect and preserve Indigenous peoples’ inherent right to believe, express, and exercise traditional religions, including ceremonial rites and access to sacred sites and objects. That policy statement is codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1996 and dates to August 11, 1978.

AIRFA is not “the moment ceremonies began,” because ceremonies never truly stopped. But it does matter that the United States needed a specific federal policy statement to address longstanding interference and suppression, and that this memory is still alive when Indigenous communities speak about appropriation and commodification of ceremonial elements.

Smudging, smoke, and the ethics of tradition

Smudging as lived practice, not lifestyle décor

In its most respectful framing, smudging is not “burning something that smells nice.” It is a way of cleansing, blessing, and preparing space—often with specific plants, words, gestures, and teachings that are community‑held rather than individually invented.

The Dakota ethnobotany guide cited earlier describes smudging around major life moments (for example, preparing a setting) and pairs the act with relational protocols: asking permission and making an offering (often tobacco) in exchange for what the earth is giving.

This emphasis on relationship is echoed in Indigenous guidance about white sage from Southern California communities. The Gabrieleno Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians frames white sage as a cultural and environmental concern because poached sage harms ecosystems and Indigenous lifeways, and it explicitly cautions that certain ceremonial elements (such as using an abalone shell and certain feathers) can constitute cultural appropriation when used outside their cultural context.

The appropriation problem has two layers

The cultural appropriation debate around sage typically has two intertwined layers:

Meaning appropriation:

When non‑Indigenous consumers call any smoke cleansing “smudging” and adopt ceremonial tools and gestures from specific Native traditions without permission, relationship, or understanding, they risk turning living ceremony into aesthetic performance. Indigenous organizations and writers have argued that this erases context and continues harms rooted in colonization.

Material appropriation (supply‑chain harms):

Even if someone tries to be respectful in intent, the physical product may be tied to illegal harvest or exploitative labor. A central point made by conservation groups is that consumers often cannot verify sourcing because the trade is opaque.

This second layer matters in Hastings because it converts “a small personal ritual” into participation in a transregional market with real ecological consequences.

White sage, poaching, and why provenance is the ethical center

California white sage (Salvia apiana) naturally occurs only in a limited region—Southern California and northern Baja.

The California Native Plant Society states that metric tons of white sage are being poached to supply international demand and emphasizes that the plant is deeply rooted in the cultures and lifeways of Indigenous communities within its natural range.

That ecological limitation is what turns “just buy sage” into an ethical trap: if demand scales faster than transparent cultivation, wild harvest becomes tempting to bad actors, and “wildcrafted” labeling can mask theft.

A widely circulated explainer from JSTOR Daily (a public humanities outlet associated with JSTOR) describes “wildcrafted” as often functioning as a euphemism for poached white sage in market contexts and observes that supply chains can run from harvesters to middlemen to wholesalers to retailers with little accountability.

Meanwhile, conservation voices note the legal dimension: the California Department of Fish and Wildlife summarizes that under California Penal Code § 384a, removing plants from public land or land you don’t own without written permission is prohibited, and that unauthorized removal can also implicate trespass or theft.

In other words, “ethical sourcing” is not only a moral claim—it may also be a question of whether the product was illegally obtained.

A respectful vocabulary shift that helps

One practical way Hastings residents can reduce harm without abandoning meaning is a vocabulary shift:

Use “smudging” when you are actually practicing within a specific Indigenous tradition you have permission and grounding to participate in.

Use “smoke cleansing” or “censing” for a personal, non‑tribal practice of burning aromatic plants for scent or intention.

That distinction shows respect for living cultural specificity while still letting people talk honestly about what they are doing. It also aligns with Indigenous critiques that the harm is not only the plant but the unmoored imitation of ceremony.

Sage species and where they grow

Sage conversations get clearer when the plants get specific.

The “sage” you can eat vs. the “sage” you burn

Below is a comparison designed for Hastings readers who want to know what they’re actually purchasing, planting, or burning. Botanical ranges reflect authoritative plant databases and plant guides; cultural notes reflect ethnobotany and Indigenous community guidance.

Common name in stores: Culinary sage / garden sage

Scientific identity: Salvia officinalis

Plant family: Lamiaceae (mint)

Where it naturally occurs: Native range in parts of southern/central Europe; widely cultivated and naturalized elsewhere

Common uses: Cooking, teas, essential oil production

Hastings-specific ethical note: Generally easiest to source ethically via cultivation; also easy to grow at home.

Common name in stores: California white sage / “white sage smudge”

Scientific identity: Salvia apiana

Plant family: Lamiaceae (mint)

Where it naturally occurs: Naturally occurs in Southern California and Baja California

Common uses: Smoke cleansing products; also traditional Indigenous food/medicine uses in its homelands

Hastings-specific ethical note: High-risk for poaching and cultural appropriation harms; prioritize farmed, fully traceable sources — or choose Minnesota “sage” alternatives.

Common name in stores: Prairie sage / white sagebrush / “white sage” (Minnesota)

Scientific identity: Artemisia ludoviciana

Plant family: Asteraceae (daisy)

Where it naturally occurs: Very widely distributed across North America; documented as present in Minnesota

Common uses: Traditional medicinal/ceremonial uses; sometimes bundled for smudges; wildlife/landscaping uses

Hastings-specific ethical note: Locally native option for acquiring/planting; still harvest respectfully and avoid overharvesting local stands.

Common name in stores: “Sagebrush” / big sagebrush

Scientific identity: Artemisia spp. (e.g., A. tridentata in the West)

Plant family: Asteraceae (daisy)

Where it naturally occurs: Primarily western North America

Common uses: Wildlife habitat; ceremonial/medicinal uses in some regions; landscape ecology

Hastings-specific ethical note: Often confused with Salvia; not the same plant family. (Mentioned here mainly to prevent mix-ups.)

Where they are grown and why that shapes supply chains

If you imagine sage as an ingredient rather than a ritual object, the supply chain becomes easier to see. Most large‑scale culinary sage markets operate through agricultural cultivation and herb processing, often tied to Mediterranean or global herb production. Research on Dalmatian sage (Salvia officinalis) essential oils, for example, discusses chemical variability and yields in Balkan/European contexts, which signals a mature cultivation-and-processing economy.

By contrast, white sage smudge products frequently travel through a less transparent chain: harvesters → middlemen → wholesalers → retailers. Multiple conservation and reporting sources emphasize that, for consumers, it can be difficult to tell whether a bundle came from cultivation or illegal harvest, especially when marketing uses terms like “wildcrafted.”

Prairie sage/white sagebrush in Minnesota sits in a different category: it is a native plant to the broader region, described as occurring in Minnesota prairies, which makes local cultivation and local purchasing more feasible and often less ethically fraught—provided that harvest is not extractive and follows permission-based practices.

A. KNOWLEDGE, PRACTICE, AND CONTEXT

Indigenous plant knowledge (place-based, protocol-based)

Connects to ethnobotany documentation (academic & archival)

Connects to ceremony & community practice

Cultural appropriation risk if decontextualized

B. GOVERNANCE AND GATEKEEPING

Regulators (plant laws, land management)

Shape what counts as legal wild harvest (permission-based)

Define/enforce boundaries against poaching (illegal harvest)

C. THREE MATERIAL PATHWAYS INTO THE MARKET

1) Cultivated production (farms, nurseries)

Processors (drying, bundling, distillation)

Wholesalers & distributors

Retail shops & online marketplaces

Hastings residents (consumers/practitioners)

2) Wild harvest (legal with permission)

Wholesalers & distributors -> (same downstream chain)

3) Poaching (illegal harvest)

Wholesalers & distributors -> (same downstream chain)

D. FEEDBACK LOOPS THAT CHANGE THE WHOLE SYSTEM

Demand signals from Hastings residents influence wholesalers/distributors and what products retailers carry.

Ethical sourcing questions from Hastings residents to retailers/marketplaces can push the supply chain toward traceability.

Economics, supply chains, and sustainability

The economics depend on the “sage category” you’re buying

Sage has multiple markets that barely resemble each other:

Food herb market (culinary sage leaves, dried spice, extracts)

Fragrance/essential oil market (distilled oils with defined chemotypes and yields)

Ritual/wellness market (bundles, sticks, “smudge kits,” associated accessories)

Those categories overlap in consumer imagination but they behave differently in production and pricing.

For example, commodity-style wholesale pricing exists for “dried sage” as a food herb; one trade listing reports recent wholesale ranges (presented as per‑kg/per‑lb equivalents) for U.S. dried sage in the high single digits to low double digits per pound, depending on region and reporting window. Treat this as directional rather than definitive pricing.

For ritual products, pricing is often per bundle length and “aesthetic,” not per pound—and the market is shaped by story, spirituality branding, and impulse purchasing. Wholesale listings for white sage sticks show per‑unit starting prices in the low single digits, but such listings rarely provide auditable supply chain proof in a way a conservationist would accept.

Example economic metrics for consumers and small retailers

Because pricing changes fast, below is best read as “what the market looks like,” not as a stable forecast.

Product type: Culinary dried sage

What is being sold: Dried leaf used for cooking

Example price signal (snapshot): Reported U.S. wholesale range in the high single digits to low double digits per lb (varies)

What that price often hides: Farm labor, drying/QA, food-grade handling and adulteration risk

Sustainability risk level: Moderate; generally best sourced via established herb suppliers and food QA systems

Product type: White sage smudge sticks

What is being sold: Bundled leaves/stems (often Salvia apiana)

Example price signal (snapshot): Retail/wholesale per-unit pricing often a few dollars each depending on size

What that price often hides: Whether plant was farmed vs poached; whether harvest involved trespass/theft; who profits along the chain

Sustainability risk level: High, due to poaching concerns and cultural harms

Product type: Loose California white sage leaf

What is being sold: Loose leaf sold by ounce/pound

Example price signal (snapshot): Example listing shows per-ounce and per-pound price points

What that price often hides: Verification of land permission, harvest season, chain-of-custody

Sustainability risk level: High if provenance is unclear

Product type: Minnesota prairie sage / white sagebrush

What is being sold: Native Artemisia grown or bundled

Example price signal (snapshot): Minnesota sources describe it as a native prairie plant and widely distributed in-state

What that price often hides: Whether it was sustainably harvested from local stands vs cultivated

Sustainability risk level: Lower to moderate; still requires respectful harvest & non-extractive practice

Wild-harvest versus cultivated: the key sustainability hinge

In sage economics, the core sustainability question is often not “Is sage sustainable?” but:

Can the seller prove cultivation or legal harvest with permission—and can they describe harvest protocols consistent with plant regeneration and community respect?

For California white sage, conservation organizations and Indigenous community statements strongly emphasize that poaching is widespread enough that “ethical sourcing” claims should be treated skeptically unless provenance is documented.

Legally, California’s plant protections include prohibitions against removing plants from public lands or land you do not own without written permission, and state wildlife guidance points to that prohibition as part of native plant protection.

For Hastings residents, the sustainability move with the highest integrity is often the simplest: choose local native “sage” options (like Artemisia ludoviciana) or cultivated garden sage (Salvia officinalis) for everyday use, and treat California white sage—if used at all—as an occasional, carefully sourced plant with verified cultivation and a respectful frame.

Science, safety, and practical guidance for Hastings residents

What science can and cannot say about sage and smudging

Scientific research intersects with sage in three main ways:

Medicinal chemistry and pharmacology of sage plants (especially Salvia officinalis).

A peer‑reviewed clinical trial in Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics tested Salvia officinalis extract in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in a double‑blind randomized design.

A broader scientific review discusses sage species’ potential cognitive effects and mechanisms (e.g., antioxidant and cholinesterase‑related hypotheses), while emphasizing limits and the need for careful interpretation.

Antimicrobial activity of extracts and essential oils (including white sage research).

Studies and reviews report antimicrobial activity of certain Salvia extracts or essential oils in vitro (lab contexts). For example, a 2019 review in Antioxidants summarizes antibacterial testing of Salvia apiana extracts in controlled assays.

A 2023 paper assessing antimicrobial activity of multiple Salvia essential oils includes S. apiana among tested oils against Listeria monocytogenes strains, again in vitro.

These studies support the general scientific point that aromatic plant compounds can inhibit microbial growth under controlled conditions—but they do not automatically show that casually burning a bundle “disinfects your home.”

Smoke studies and the “sage cleans the air” claim.

A frequently cited paper (Nautiyal et al., 2007) reports that “medicinal smoke” reduced airborne bacteria in a confined setting.

However, science fact‑checking notes that viral social claims often misrepresent what was actually burned in that study and that the evidence base is not robust enough to claim that burning “sage” reliably purifies indoor air in real‑world conditions.

In short: science can meaningfully describe plant chemistry, some pharmacological potentials (especially for ingestion/extracts), and indoor air pollution from burning. Science is not a referee for spiritual meaning—and it should not be used as a marketing weapon to excuse harmful sourcing or unsafe indoor smoke exposure.

Indoor air quality: treat smudging like any combustion source

Burning sage produces smoke. Smoke contains fine particles (PM2.5) and a complex mixture of gases, which is why many schools, dorms, and residences restrict candles and incense. Minnesota fire code guidance, for example, notes that candles and incense are prohibited in certain dormitory sleeping units due to life safety risks.

Health and engineering literature on indoor air repeatedly identifies incense burning as a significant indoor particle source, with PM2.5 emissions and particle characteristics that shape inhalation exposure.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains that indoor particulate matter can decrease lung function and aggravate asthma, and it lists combustion sources as indoor PM contributors.

This leads to an evidence‑aligned, practical principle:

If you smudge, reduce dose and increase ventilation—especially around children, elders, pets, and anyone with asthma or heart/lung disease.

AI image by HastingsNow.com

Best practices for smoke cleansing in a Hastings home

This is written for safety and ethical alignment, not as a claim that you “need” to do this.

Preparation and ethics

Name what you’re doing. If you are not participating in a specific Indigenous tradition with permission, call it “smoke cleansing,” not smudging.

Know which plant you have. Ask whether the bundle is Salvia apiana (California white sage) or Artemisia ludoviciana (prairie sage/white sagebrush), because the ethical and ecological stakes differ.

Ask provenance questions and expect real answers. For S. apiana, look for cultivation claims that include where it was grown and how it was harvested; for wild harvest, ask what land permission existed. This aligns with conservation concerns about opaque trade.

Treat ceremony as relationship, not consumption. Dakota ethnobotany teaching emphasizes permission and offering as ways of relating to plants rather than extracting from them.

Step-by-step safety

Ventilate first. Crack a window or door. If you can, run a bathroom fan or kitchen hood (vented). This follows general indoor PM reduction logic: reduce concentration and duration.

Use a fire‑safe vessel. A ceramic bowl, metal dish, or other nonflammable container; keep it on a nonflammable surface away from curtains and paper. Fire authorities emphasize that open flames and incense/candles carry life safety risks when mishandled.

Light briefly, then smolder—don’t flame. Many smoke cleansing practices rely on smoldering rather than a sustained flame, reducing immediate flame risk and limiting smoke production. (This is a harm‑reduction adaptation, not an authenticity claim.)

Keep it short. Think “seconds to a couple of minutes,” not “fill the room.” The health‑relevant variable is total smoke dose.

Extinguish completely. Use sand, water (if appropriate for the vessel), or firm pressing into a fire‑safe medium until no smolder remains. Avoid leaving smoldering material unattended. Open burning statutes prohibit smoldering outdoor fires in many contexts; while indoor smudge sticks aren’t the same legal category, the safety logic travels well: no unattended smolder.

Air out afterward. Keep ventilation going for several minutes; consider a HEPA air cleaner if you have one, as EPA indoor PM guidance emphasizes actions to reduce indoor particle exposure.

If you live in multi-unit housing or regulated spaces

Check fire code/building rules. Minnesota fire code guidance explicitly restricts candles/incense in certain occupancies (e.g., dormitory sleeping units). Other properties may have similar policies.

Consider reasonable accommodations frameworks. If smoke cleansing is part of a sincerely held religious practice (for example, Indigenous spiritual practice), workplace accommodation law under Title VII involves “reasonable accommodation” unless it creates undue hardship, per EEOC guidance. Housing accommodations may involve different laws and facts; this is a cue to ask, not a guarantee.

Smoke-free alternatives that preserve intention

If your goal is “transition, blessing, cleansing” rather than “smoke,” consider:

A short spoken intention/prayer paired with opening a window (symbolic + practical).

A bowl of locally grown culinary sage leaves for scent without burning (not a ceremonial replacement; a sensory anchor).

Cleaning the space physically first, then using a minimal smoke approach (ethical alignment: do not outsource real-world care to metaphor).

AI infographic by HastingsNow.com

Contemporary teachers, “sage gurus,” and what credentials can (and cannot) mean

Because sage sits at the crossroads of botany, ceremony, wellness commerce, and identity, “teachers” come in different categories.

Indigenous knowledge holders and community teachers:

Credentials here are often relational: community recognition, lineage, responsibility, and protocols—not a certificate that can be purchased. AIRFA’s legal history provides context for why communities may protect ceremonies from commodification.

Clinical herbalists:

Credentialing is voluntary but structured. The American Herbalists Guild describes criteria for its Registered Herbalist credential involving specific amounts of herbal education and clinical practice experience.

Aromatherapists:

The University of Minnesota resource “Taking Charge of Your Health & Wellbeing” notes there is no national aromatherapy certification, though organizations provide educational guidelines.

The National Association for Holistic Aromatherapy publishes education standards (e.g., minimum hours and curriculum elements for certain levels).

Acupuncturists and Chinese herbology practitioners:

National certification bodies exist in this space; for example, occupational certification listings describe NCCAOM credentials as indicating competency in Oriental medicine, which may interact with state licensing.

Reiki and “energy” practitioners:

Reiki organizations note ongoing debates and periodic attempts at regulation, which implies that legal status and requirements can be jurisdiction-dependent rather than standardized. Treat any “Reiki certification” as a lineage/training marker, not a universally regulated license.

Practical takeaway for Hastings residents:

If someone sells “smudging lessons” or “sage mastery,” the most useful questions are:

What tradition are you teaching? What community are you accountable to? What plant species are you using and how is it sourced? What safety protocol do you teach for indoor air quality and fire prevention?

Local vendor profile for Hastings residents

What Hastings residents can do anyway—ethically and practically:

When you visit, ask: “Is this prairie sage (Artemisia ludoviciana) or California white sage (Salvia apiana)?”

Ask where it was grown and whether it was cultivated; if wild harvested, ask what land permission existed (especially relevant for California white sage because of documented poaching concerns).

Ask what guidance they give for ventilation and indoor safety; a responsible retailer should acknowledge indoor particulate concerns and fire risk management.

Contact and visit information Pure Serenity Wellness Center:

Address: 202 2nd Street E, Hastings, MN 55033

Phone: 651-983-9776

Email: pureserenitymn@gmail.com

FAQ

-

Often, no. Minnesota “white sage” commonly refers to Artemisia ludoviciana (white sagebrush/prairie sage). Many mass‑market smudge sticks labeled “white sage” are Salvia apiana from Southern California/northern Baja.

-

The ethical concern is less “anyone burning any plant” and more about (a) borrowing specific Indigenous ceremonial elements without relationship/permission and (b) participating in harmful supply chains—especially for Salvia apiana. Indigenous organizations explicitly describe appropriation concerns around ceremonial items and protocols.

-

“Smoke cleansing” or “censing” communicates what you’re doing without claiming a ceremony name tied to specific Indigenous practices.

-

AIRFA (Aug. 11, 1978) established federal policy to protect and preserve Indigenous peoples’ right to exercise traditional religions and ceremonial rites, acknowledging that federal policies had often interfered. Government and museum sources describe 1978 as a key legal milestone.

-

Conservation organizations state that poaching is occurring at significant scale and that international demand is driving theft; Indigenous community statements describe poaching harms and warn that unlabeled products may be poached.

-

Look for transparent cultivation claims with traceability (where grown, by whom, harvesting methods). Be cautious with vague “wildcrafted” claims given reporting that the term can mask poaching.

-

A study on “medicinal smoke” reported airborne bacteria reductions in a confined setting, but science fact‑checking warns that viral claims often misrepresent what plants were burned and that the evidence base does not support sweeping “burn sage to sanitize your home” claims.

-

Smoke increases indoor particulate exposure. EPA notes indoor PM can aggravate asthma and decrease lung function, and incense literature identifies smoke as a significant PM2.5 source. For sensitive individuals, consider smoke‑free alternatives or strict ventilation and minimal duration.

-

No. Minnesota fire code guidance prohibits candles and incense in certain occupancy sleeping units (e.g., Group R-2 dormitory sleeping units), and many landlords/campuses set stricter rules.

-

Workplace religious accommodation under Title VII involves a “reasonable accommodation” framework unless it imposes undue hardship, per EEOC guidance. How that applies depends on facts (safety, ventilation, coworkers’ health needs, etc.).

-

Prairie sage/white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana) is documented as a Minnesota native plant found in prairies and described in plant resources for the state.

-

Start with (1) local plants where possible, (2) transparent sourcing questions, (3) minimal smoke and good ventilation, and (4) language that doesn’t claim ceremony you’re not part of.

References

Primary and official legal / policy sources

American Indian Religious Freedom Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1996 (Cornell Law / LII).

Public Law 95‑341 (AIRFA), U.S. Government Publishing Office via GovInfo.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission guidance on religious accommodations in the workplace (Title VII).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency indoor particulate matter sources and health effects.

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources open burning permit information (includes definitions for campfire/ceremonial purposes outdoors).

Minnesota Statutes on open burning restrictions (Revisor of Statutes).

California Department of Fish and Wildlife laws protecting native plants (references Penal Code § 384a).

California Penal Code § 384a text (California legislative codifications).

Botany and distribution

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Plants of the World Online: Salvia officinalis distribution.

Kew Plants of the World Online: Salvia apiana distribution.

USDA PLANTS Plant Guide for Salvia apiana (white sage): description, habitat, propagation.

USDA PLANTS Plant Guide for Artemisia ludoviciana (white sage/prairie sage): ethnobotany notes, distribution, chemistry cautions.

Minnesota Wildflowers: Artemisia ludoviciana occurrence in Minnesota.

University of Minnesota Season Watch: “White sage” in Minnesota prairies.

Ethnobotany and cultural context

Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (public domain text): references to “white sage” and smudging practices.

Dakota ethnobotany guide (academic PDF) describing four sacred plants and smudging protocols.

Gabrieleno Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians statement on white sage preservation, poaching harms, and appropriation concerns.

Minnesota Historical Society MNopedia and Fort Snelling resources on Dakota place-based history and Bdote context.

Sustainability, supply chains, and poaching reporting

California Native Plant Society white sage protection page (poaching scale, limited natural range).

United Plant Savers discussion of white sage trade and enforcement events.

High Country News reporting on white sage poaching and trade opacity.

JSTOR Daily reporting on “wildcrafted” labeling, legality concerns, and supply chain pathways.

Scientific literature on sage and smoke/air quality

Nautiyal et al. (2007) “Medicinal smoke reduces airborne bacteria” (PubMed).

Science Feedback review noting misinterpretation of “burning sage purifies air” claims.

Yadav et al. (2022) review on health and environmental risks of incense smoke (PMC).

Ofodile et al. (2024) PM2.5 emissions characterization from incense burning (PMC).

Akhondzadeh et al. (2003) randomized trial of Salvia officinalis extract in Alzheimer’s disease (PubMed).

Lopresti (2016) review: potential cognitive effects of Salvia (PMC).

Antioxidants review summarizing antimicrobial and immunomodulatory aspects of Salvia apiana (MDPI).

Professional credential frameworks

American Herbalists Guild Registered Herbalist criteria (voluntary credentialing).

National Association for Holistic Aromatherapy educational standards (hours/curriculum elements).

University of Minnesota Taking Charge: no national aromatherapy certification (consumer guidance).

Local Hastings-specific vendor information

Pure Serenity Wellness Center contact page with address/phone/email.

Pure Serenity website home page describing services and general retail offerings (crystals/spiritual tools; no inventory specificity).

City of Hastings document referencing massage therapist renewals including Ericka Love at the downtown address.

Downtown Hastings directory listing the wellness center.